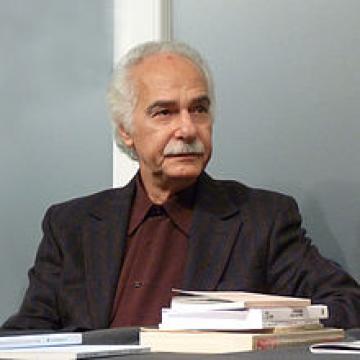

Conversations with Moroccan Poet and Writer Abdellatif Laâbi

On February 20-21, the University of Oxford hosted a two-day event with Moroccan poet Abdellatif Laâbi. Organized with the generous support of The Ertegun Graduate Scholarship Programme in the Humanities and the Maison Française d’Oxford (the French cultural centre in Oxford), the event provided a unique opportunity to discuss and engage with the work of one of the major voices of Francophone poetry.

Born in Fez in 1942 under the French protectorate, Laâbi was only fourteen when Morocco gained its independence in 1956. Laâbi taught French in Rabat and cofounded in 1966 with a group of Moroccan poets and artists the journal Souffles-Anfas, one of the most influential platforms for cultural and political production in postcolonial Africa and the Global South. A political activist in the Moroccan Left, Laâbi was arrested in 1972 and spent more than eight years in prison. After an international campaign for his release, he left Morocco and went into exile in France. Laâbi has published a wide range of works including poetry collections, novels, essays, autobiographies, children’s books, and translations, as well as a series of articles and interviews. In 2009 he was awarded the prestigious Goncourt Prize of Poetry and in 2011 the Grand Prix de la Francophonie de l’Académie Française. His works have been translated into English, Spanish, German, and Italian, among other languages.

The first day of the event was held at Maison Française and opened by Jane Hiddleston (Exeter College) who offered a synthetic introduction of Laâbi’s trajectory and literary production. The first panel, chaired by Toby Garfitt (Magdalen College), included talks by Andy Stafford (University of Leeds) and Khalid Lyamlahy (St Anne’s College) on the motif of light in Laâbi’s work. In two equally enthusiastic presentations, Stafford discussed the at once ambivalent and rich meaning of a series of occurrences of the word “soleil” (“sun” in French) in Laâbi’s early poetry, while Lyamlahy reflected on the presence and absence of light in Laâbi’s writing, demonstrating how the poet recovers, protects, and brings light to his readership. For the Moroccan poet who has long lived behind bars, light is a source of hope, inspiration, and generosity. As he writes in one of his prison poems from 1978:

Bonjour soleil de mon pays

qu’il fait bon vivre aujourd’hui

que de lumière

que de lumière autour de moi

Bonjour terrain vague de ma promenade

tu m’es devenu familier

(Good morning sun of my land

how good it feels to be alive today

so much light

so much light around me

Good morning empty exercise yard

you have become familiar to me)

This extract is written as a dialogue between the jailed poet and the Moroccan sun. By repeating the word “lumière” (“light” in French), Laâbi celebrates life and creates a sense of freedom that resists incarceration and confinement.

The second panel took the form of a conversation between Khalid Lyamlahy and Laâbi’s wife Jocelyne who is also a writer. Jocelyne has published a historical novel, an autobiography in which she recounts her life in Morocco and struggle for Abdellatif’s release, in addition to several collections of Moroccan tales which she gathered and translated into French. During the conversation, Jocelyne explained how she came to writing, commenting on her interest in Moroccan popular culture and, more broadly, the history of the Arab world. She also read some excerpts from the new edition of her Moroccan tales, Avec la rivière mon conte s’en est allé (Al Manar, 2018) which means “With the river my tale went away”, a closing formula used by Moroccan storytellers at the end of their tales.

In the third and final panel, Abdellatif Laâbi was interviewed by Catriona Seth (All Souls College) before giving a brief talk in which he discussed the challenges of being a writer “from the periphery” and how this position shapes his approach to poetic creation and language. Significantly, Laâbi described his literary career as a “miracle”, a word that refers to both his background as the son of a Moroccan craftsman whom nothing predestined to become a writer, and to the sense of wonder and sensitivity that characterizes his poetic work. To close, Laâbi read some excerpts from his poetry before signing his English-translated books, including The Rule of Barbarism (2012), The Bottom of the Jar (2013), and his recent bilingual anthology In Praise of Defeat (2016), all published by Archipelago Books in New York, and Beyond the Barbed Wire (2016), published by Carcanet Press in the UK.

The second day of the event was held at the Ertegun House. It opened with a roundtable on language and politics in North Africa with the contributions of James McDougall (Trinity College) and Kaoutar Ghilani (Lady Margaret Hall). Both discussed, in the presence of Laâbi, the evolution of language politics in the Maghreb, and the effect of colonialism and nationalism on linguistic dynamics in the region. McDougall and Ghilani provided an instructive and complementary overview of the Arabisation policy and the teaching of foreign languages in both Algeria and Morocco, while Laâbi reaffirmed the necessity of recognising local dialects and promoting linguistic diversity in the region.

The second part of the event was dedicated to a discussion between Laâbi and his translator André Naffis-Sahely on the practice and values of translation. Drawing on his experience as a translator of Palestinian Arabic poetry into French, Laâbi defined translation as an act of love, dialogue, and deep understanding of the original text. Similarly, Naffis-Sahely drew on the legacy of the late British poet and translator Sarah Maguire to argue that translating consists in taking not only an aesthetic but also an ethical position. The discussion was then followed by a bilingual reading of Laâbi’s poetry in both French (by Laâbi) and English (by Naffis-Sahely).

This two-day event was a unique opportunity to engage with the deeply humanist and thought-provoking voice of Abdellatif Laâbi. Subtle and powerful, sensuous and rebellious, his poetry is not only a record of a life of commitment and dignity, but also a call to remain vigilant and reinvigorate the dynamics of resistance in an age of violence and intolerance. Laâbi reminds us that writing is the most valuable act of sharing. In his words,

Ton écriture est ton seul bien, celui que tu n’as jamais monnayé et que personne n’a jamais pu acheter. Et ne crois pas que tu en sois propriétaire. Ce bien n’est tien que dans la mesure où tu le distribues chaque jour, chaque nuit, surtout quand tu traverses les périls.

(Your writing is your only asset, the one that you have never sold and that no one has ever been able to buy. And do not imagine that you are its owner. This asset is yours only so long as you share it every day, every night, and especially when you are crossing perilous territory)

Khalid Lyamlahy