Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons; A Reimagining

Last Friday night, Ertegun took a trip to Shakespeare’s Globe to see the ‘Four Season’s Reimagined,’ Max Richter’s fresh take on Vivaldi’s masterpiece. The performance combined Richter’s composition with the ingenuity of Gyre & Gimble’s narrative puppeteering, an unlikely pairing that recalls musicals—think War Horse, or the Lion King—more than classical concerts.

The Globe’s ‘Four Seasons,’ as most people were surprised to learn, was my first classical music performance. Growing up, my parents had always played WETA 90.9 in the car, so I spent my morning rides to school and evening shuttles to soccer practice nodding along to the soft hums of violins, cellos, the occasional flute. Not that I can really distinguish between Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, and Strauss. And, as I learned just before the Globe performance, Verdi and Vivaldi are not, in fact, the same composer. Classical music, for me, has always served as a type of background, its own kind of soft, soothing chatter. When I hear the sharp draw of a bow, a quick drop in octaves, I think of Sunday mornings with my dad, en route to Krispy Kreme; or late nights in the library, cranking out my term paper. Sometimes I think of Easter dinner with my grandparents, music floating through our kitchen and into the dining room along with asparagus and buttered rolls.

But I was hoping, by going to the ‘Four Seasons,’ that I might get a better sense of why, for some people, music isn’t just background noise, second to the events of life. Nietzsche thought that music is the art form that most speaks to the human soul, to the joy and trauma of human existence. I’ve always found that feeling in front of paintings: put me in front of the Raft of the Medusa or Rainy Day, and I’ll instantly become quiet, subsumed, drawn into the world of the painting in front of me and out of my reality on the gallery floor. I assumed that because visual art spoke to me, perhaps music just didn’t. But feeling depleted by the end of term, ready for a little shake up, I wanted to give Vivaldi a shot.

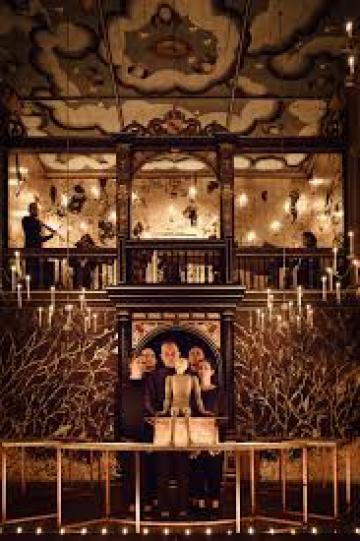

The theater was stunning. The Sam Wanamaker playhouse is modeled on Blackfriars Theatre, its original plan known from extant drawings housed in Worcester College, Oxford. The atmosphere was warm and intimate, lit only by candles. The stage was covered in a luscious, flickering gold that made me feel like I was walking inside a Gustav Klimt painting. The effect was otherworldly, an interesting move for a composition modeled on the earthly seasons. Gold strikes me as an optimistic color, a raising of man into another realm, a realm not determined by the red and browns of autumn, the blues of winter, the pinks and greens of spring and that beautiful, hot yellow of summer.

The performance started slowly, a few minutes of clear music. After fifteen minutes, the performers moved large, golden tables onto the stage and began shifting them in perfect circles, crafting different geometric configurations. And then, finally, the puppets appeared, each one manipulated by at least two or three performers at once. Three men to move one—a metaphor, perhaps, for the narrative that would unravel onstage.

I meditated on the performance in front of me. And as the notes wafted into the warm, glowing air, as the performers took their silent footsteps around the stage and as the puppets jerked to life, running from glowing table to glowing table, I thought. It’s fitting perhaps, that during Vivaldi’s ‘Four Seasons’ I ran from memory to memory, moving in and out of them like leafy doors into secret forests, finding my own vibrant, lonely gardens at the roots of my search. I watched the purple paper butterflies crackle onstage and I thought about the bluebells that grew in my backyard in Virginia; I thought about the puddles that pooled under our makeshift tire swing and how they would gleam in the early light, when my sisters and I padded out into the dewy grass, children alone with the morning. When autumn came, those deep cello strokes sounding notes of mourning, of contemplation, I thought about grief, about the incense at Sacré-Coeur, about the wooden beams of the church in Passaic where we left my grandfather. I thought about the naivety of youthful optimism, and how necessary it is. In Spring, as the wooden puppets sat on a park bench and first reached out to one another, tentatively, full of shy desire, I thought about the first time I fell in love, how all-encompassing, how light that feeling was. I thought about the baby girl I might have one day, and how she might smile and stomp through daffodils, about how I will protect her from the white butterflies—the bad memories, the ghosts. And when the music started racing, when the youngest puppet swam deep into a pool, finding peace only by diving in, I thought about the performance itself: plunging us into the music, the narrative, that gold which reflected and refracted us, forcing us to fight through our own emotions, our personal slides of past lives, of memories. They whizzed by us like a lecture on high-speed, until we reached that placid part of the water, deep and dangerous, but utterly peaceful. A spot I fought to get to, and from which, like the puppet, I realized I had to emerge, when eventually the spell was broken and I came up for air.

For me, art isn’t complicated. The best works of art, I’ve found, are the ones that make you feel. Sometimes they reach out and grab you, shocking you out of your reality; sometimes, as for me, they plunge you deeper into yourself. The combination of Richter’s beautiful composition, the musicians’ expressive performance, and the carefully managed, tightly executed puppeteering combined to create a sort of ‘total artwork’ that emanated off the musicians’ bows, the puppet’s smooth wooden bodies, and the performer’s soft movements. Halfway through the performance, stunned at my blurry vision, the big bright tears welling up in my eyes, catching and trapping the candlelight and lending the whole performance a hazy golden aura, I looked next to me and Frazer was crying too. Across the theater, Kaotaur and Alifya sat enraptured, never taking their eyes of the stage. Everyone in the theater breathed in those moments, lived each concerto, each peak and each devastating fall, together. Wagner talks about a ‘total artwork,’ a gesamtkunstwerk, as the one hope for a society in degradation. By connecting people with people and people with beauty, art can redeem. The ‘Four Seasons Reimagined’ made me believe in that again.

Emily Cox