Music of the Ertegun Night; or, Why Kafka would kill for my desk

There comes a time when even the most steadfast procrastinator has to turn and face the music. If you’re like me, then that time is invariably the late evening. And the music is usually not music at all. Usually, it’s just a desk.

Those who have observed my movements around Ertegun House over the past six months could tell you that my desk and I have something of a love/hate relationship. I spend a worrying number of hours studiously avoiding my desk by doing almost anything that requires my presence in the kitchen: eating works nicely, but complaining and gazing absent-mindedly out the window are also personal favourites. My desk spends an equally pathological amount of time exerting its tyrannical power over me from afar – presumably from its habitual spot in the upstairs office, but who knows what it really gets up to when I’m not around. All I can say for sure is that it delights in sending me regular waves of pure guilt until I finally trudge upstairs to find it there still, right where I left it.

The ‘droghte of March’ – a phrase that takes on its true and terrifying meaning only when translated as ‘the end of Hilary Term’ – has recently forced me to spend more time just hanging out with my desk than I have in months (since the last end-of-termly cataclysm, to be exact). And in the process, something magical has happened: I’ve been reminded of just what makes this desk unique in all of Oxford. My desk and I have fallen in love all over again.

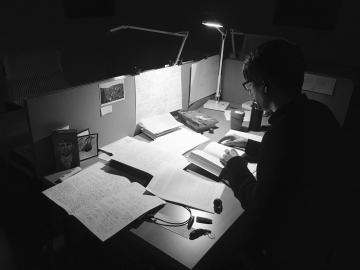

It should come as no surprise that this illicit courtship has taken place at night, under cover of darkness. To me, the real wonder of Ertegun House is the fact that this is possible at all. Unlike most other places in Oxford, the House doesn’t fall dutifully silent at dusk; instead, all manner of nocturnal creatures emerge from its gorgeous Georgian woodwork. The small cult of nightwalkers who only now are waking up can be heard chuckling, Cheshire-cat-like, in the kitchen, celebrating the communion of those whose circadian drums beat well and truly out of time. Their jovial tones echo ghostlike through the hallways, dark silhouettes in the yellow window casting shadows up the study walls. In the half-light, the words which only this afternoon stared mockingly from their sprawling mind-maps begin to dance: pirouettes in directions I never expected, balletic leaps into new formations that I race to keep up with, scribbling across page after page. In the witching hour, my desk has come to life.

One of the best teachers I ever had implored us – a gaggle of eager, fresh-faced undergrads – not to do the required reading in the library. It was Wordsworth and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads, and if this doomsday teacher was to be believed, it would be as meaningless and distorted under the glare of the library lights as that mermaid egg in Harry Potter when they crack it open in the Common Room. Instead, he suggested midnight candlelight and a bottle of cheap red wine – bringing the poems back out of synch with an academic nine-to-five, and into the creative space where they began, like listening to mermaid voices underwater.

Creative spaces come in all shapes and sizes, of course. In German studies, we don’t know larks and night owls; we know Thomas Manns and Kafkas. The former wrote religiously from nine till noon; the latter sat down to his desk each night at eleven and worked into the small hours. (Prague had Kafka, Ertegun House has Khalid). One of Kafka’s most famous stories, ‘The Judgement’, was written in a single night and in one sitting. Does it have to be read that way to grasp its brilliance? Of course not. But the knowledge of its vampiric genesis does afford me, a frequent victim of the blood-sucking all-nighter, some life-restoring hope as my own uninspired Kafka essay contorts before my eyes. (Kafka, for his part, once remarked with a smile that ‘there is hope, just not for us’).

One thing’s for certain: Kafka would have given his fangs for a desk in Ertegun House. He was forever complaining about being kept from writing: by his day job as an accident insurance lawyer, by food and sleep, by noisy siblings. The extraordinary privileges of life in the House – the gift of free time and, most importantly, a desk of one’s own, day or night – were the stuff of daydreams for him. We’ll never know what Kafka would have done with these gifts. My own fond theory, for what it’s worth, is that he would have darkened everyone’s day in the kitchen, drunk too much coffee, bitten his nails in guilt, and gone abashedly upstairs to his desk each night at eleven. Anything else would have been far too absurd a metamorphosis.

Ertegun House is a safe haven for all those circadian misfits who might otherwise stand accused by library opening times and Theresa May of being ‘monstrous vermin’. The life-blood of the Humanities, after all, is creativity, the ability (or compulsion) to see the world in a different light – even if it means staying up all night from time to time. As I bask in the lamplit pool of my desk, I listen to the silence of the House around me, and it begins to sound like music after all.