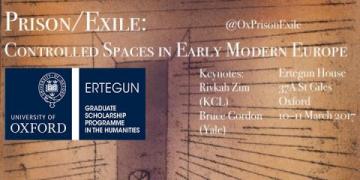

Controlled Spaces in Early Modern Europe

In the first instantiation of the Ertegun House Seminar in the Humanities, Wole Soyinka recalled his time in prison during the Biafran War. Deprived of human contact and intellectual stimulation, he wrote poetry in Spanish, scrawled on toilet-paper dowels for lack of writing materials. It was for the sake of understanding of such human moments, such strivings of the spirit and intellect amid the direst of circumstances that more than fifty scholars gathered at Ertegun House for an interdisciplinary conference on imprisonment and exile in the early modern period.

The original impetus for the conference came from my M.Phil. dissertation examining the prison notebooks of the Tudor bishop Stephen Gardiner. With the encouragement of the then-Ertegun Director Bryan Ward-Perkins and the collaboration first of a fellow postgraduate student in ecclesiastical history, Anik Laferrière, and then of an incoming Ertegun scholar, Chiara Giovanni, the initial idea grew to encompass exile, monastic enclosure, and other forms of confinement and restriction. This proved of immense value in endowing our conference with a unique identity, one with an added value beyond other gatherings dedicated to only one of these spatial modalities or confined to only one discipline or geography.

From the beginning, we hoped to gather papers that were interdisciplinary in method and international in focus. It is a matter of great gratification that we succeeded: our nearly forty speakers ranged from postgraduates to Regius Professors, their papers exploring sung metrical Psalms and the organizational difficulties of early modern prisons for women, imprisoned Italian Dominicans and Hungarian utopian thought, Jesuits in Ethiopia and rhyme as a kind of prison in English verse. Furthermore, we made a conscious decision not to divide panels along purely national or disciplinary lines, but rather to link them by theme, with the aim that conversations might occur between those studying prisoners and those studying exiles, and between the different disciplines represented.

The same diversity obtained in our plenary speakers, Professor Rivkah Zim of King’s College, London, and Professor Bruce Gordon of Yale University and the Yale Divinity School. Prof. Zim, the author of an innovative book on prison writing across two millennia, opened the conference with a wide-ranging exploration of the political significance of writing from prison in early modern England. Prof. Gordon, perhaps the world’s foremost authority on John Calvin, drew out the complexities of imprisonment and exile in the writings of the Genevan reformer (a decades-long exile from his native France).

The conference would quite simply not have been possible without the generous support of Ertegun House. The Programme’s funding permitted us to bring Prof. Gordon from the United States of America, to provide both our keynotes accommodation in Oxford, and to dispense with any fee for attending the conference. This last point proved an unmitigated success, as it enabled yet more scholars from around Oxford and beyond to join the discussion. What is more, the involvement of the Programme went beyond financial support and the use of our beautiful facilities: besides Chiara and myself, Ertegun House Director Rhodri Lewis chaired our first plenary session, current Scholar Rachael Hodge presented a paper on the “prison scene” in King Lear, and recent alumna Molly Corlett (currently a PhD student at King’s College, London) chaired a session on communities in exile. House Administrator Jill Walker also offered unflagging support before and throughout the conference.

It is difficult to fathom that that first nebulous idea floated more than a year ago took shape. The universally positive reactions from attendees, speakers, and chairs have been beyond my wildest expectations. The insights shared over those two days will prove fundamental to my current work and have already inspired myriad imaginings of future projects. The experience was nothing short of transformative, an opportunity afforded only by the unique possibilities of the Ertegun Scholarship.

Spencer Weinreich